Can you please Introduce yourself?

My name is Dr. David Oladele, a Chief Research Fellow, Consultant, Public Health Physician, and the Head of Department (HOD) Clinical Sciences Department of the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research (NIMR)

We are aware of the ongoing research on TASSH; please tell us more about it.

The research is titled “Integration of Hypertension Management into HIV Clinic using Task Strengthening Strategy (TASSH) in Lagos, Nigeria.”

It is a research project sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institute of Health (NIH) in the United States.

It is a collaboration between three institutions:

- Nigerian Institute of Medical Research, NIGERIA

- Saint Louis University, Missouri, USA

- New York University, Langone, New York, USA.

The project has three Principal Investigators (PIs):

- Prof. Oliver Ezechi from NIMR

- Prof. Olugbenga Ogedegbe from New York University

- Prof. Juliet Iwelunmor

from Saint Louis University

from Saint Louis University

The research addresses the challenge of providing care for hypertension among patients diagnosed with and living with HIV. With improved access to antiretroviral (ARV) medication, individuals living with HIV are living longer, and many of them are at increased risk of developing non-communicable diseases, including hypertension, a significant risk factor for cardiovascular diseases and stroke. The project seeks to integrate the treatment for hypertension into HIV clinics in Lagos, Nigeria. This is because, currently, patients living with HIV receive care for hypertension in different locations than where they receive HIV treatments. The goal is to bring together the treatment for hypertension and HIV at the same clinic by actively screening HIV-positive patients for hypertension and ensuring timely diagnosis and care.

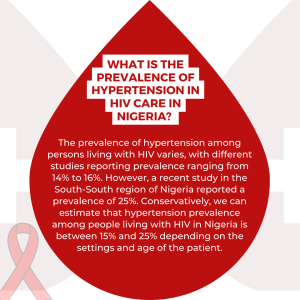

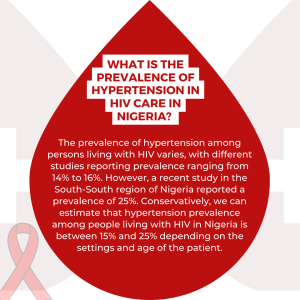

What is the prevalence of Hypertension in HIV care in Nigeria?

What is the prevalence of Hypertension in HIV care in Nigeria?

The prevalence of hypertension among persons living with HIV varies, with different studies reporting prevalence ranging from 14% to 16%. However, a recent study in the South-South region of Nigeria reported a prevalence of 25%. Conservatively, we can estimate that hypertension prevalence among people living with HIV in Nigeria is between 15% and 25% depending on the settings and age of the patient.

How does Hypertension impact the health outcome among HIV patients in Nigeria?

Hypertension plays a significant role in shaping the health outcomes of HIV patients in Nigeria. HIV is an infectious disease that affects the immune system, and without proper treatment, it can lead to opportunistic infections and potential mortality. However, thanks to access to HIV treatment facilitated by initiatives like the PEPFAR (U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief) Funding since 2004, many HIV-positive patients now could receive proper care. In Nigeria, we have successfully decentralized HIV care, transitioning from only three centers in Lagos as of 2002 (Nigerian Institute of Medical Research, 68 Military Hospital, Yaba, and Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Idi Araba) to over 60 comprehensive primary healthcare centers in Lagos State alone. This decentralization and improved access to medications and healthcare commodities have resulted in longer and more productive lives for HIV patients.

The common cause of death among HIV patients before now were opportunistic infections such as tuberculosis, diarrhea diseases among others; however, due to improved access to HIV care and subsequent immune system improvement, there is an increase in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) among HIV-positive patients resembling what is observed in the general population. Therefore, if we do not address the issue of NCDs, particularly hypertension, among HIV-positive patients, the progress achieved in HIV treatment could be undermined. Hypertension stands out as a significant NCD, and it is crucial to screen and diagnose hypertension in HIV-positive individuals to provide timely treatment and control their blood pressure. By effectively managing hypertension, we can prevent the development of hypertension-related diseases such as cardiovascular diseases and stroke, thereby improving the overall quality of life and health outcomes for HIV patients. Addressing the burden of hypertension in HIV-positive individuals is vital to prolonging and enhancing their quality of life, ultimately leading to better treatment outcomes.

What are some of the most significant outcomes from the research so far, and what do they suggest about the effectiveness and feasibility of TAASH?

Integrating hypertension care into HIV clinics using the TASSH strengthening strategy has yielded noteworthy results thus far. The task-strengthening strategy is an off-shoot of Task shifting, defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “decentralizing treatment from highly skilled healthcare workers to those with less specialized training, thereby addressing the challenges of limited human resources for health.” Nigeria currently faces a brain drain, with many doctors and nurses leaving the country, resulting in a scarcity of healthcare workers to cater to the substantial population. In response, the TASSH strategy allows nurses and community health officers to play a vital role in screening patients for hypertension, providing lifestyle counseling, administering treatment, and referring severe cases to doctors.

The program is a clustered randomized trial meaning that we are working across 30 primary healthcare centers in Lagos State, Nigeria. Fifteen centers are assigned to receive the intervention, while the remaining 15 receive standard care. After 12 months, the treatment outcomes for hypertension will be compared between the two groups. The intervention involves a practice facilitation strategy, where nurses and community health officers in the selected primary healthcare centers receive additional support from senior healthcare workers. This support includes reminders for patient screening, counseling on lifestyle changes, and dietary habits using evidence-based frameworks like the 5 A’s and C’s. The trial aims to assess the impact of practice facilitation, akin to a coaching strategy, on blood pressure changes in the intervention group compared to the standard care group.

So, what we have learned so far is that for this program to work, there is a need for intense collaboration between researchers and the health system in the State. Currently, the institute is collaborating actively with the Primary Health Care Board in Lagos State as well as Lagos State AIDS Control Agency (LSACA) to intensify the centres and to train health care workers working at these Primary Health Cares (PHCs) at different times both baseline and other training and to be able to improve their skills to make the diagnosis of hypertension and monitor patients on treatment and refer severe cases to doctors. Additionally, the project has donated the necessary screening equipment to these centers through the Lagos State Primary Healthcare Board. This research has highlighted the need for active collaboration between researchers, the health system, doctors, and nurses in primary healthcare centers to ensure the effective implementation and sustainability of the task-shifting strategy in Lagos State, Nigeria.

Furthermore, the challenge of healthcare worker migration, resulting in a reduced number of doctors and nurses to address the growing patient demand, has been recognized. To address this, healthcare workers have been advised and trained to triage and prioritize patients effectively, thereby managing their workload without compromising the quality of care provided. This approach has shown us and the Lagos State Health Management that there is a need to bring hypertension care into the HIV clinic. This integration provides the opportunity to address the double burden of infectious and non-communicable diseases, leading to improved quality of life and long-term health outcomes for patients.

Can you speak to the importance of international collaboration and cooperation in your experience and the opportunities available for other potential researchers in NIMR?

The TASSH project is a collaborative effort between NIMR, New York University, and St. Louis University. The grant was awarded to the three institutions, and we have teams working on this project from the three institutions. So, what that has brought to bear is a robust north-south collaboration on this project, meaning that experiences of researchers working at New York University and St. Louis University have been cross-fertilized with researchers in Nigeria to be able to implement this project in the context of the Nigerian health system because the Nigeria situation is very peculiar.

A similar project to TASSH-Nigeria was implemented in Ghana before the Nigerian study, but the Ghana terrain is entirely different from Nigeria’s. The health system there is different, so there is a need to domesticate the research approach in the Nigerian context, and that is a lesson we have learned that collaboration is needed. This will allow researchers here to liaise with researchers outside the country with a resultant cross-fertilization of ideas on the best way to address challenges that arise during the course of the project implementation and also to build the capacity of local researchers through exposure to education outside the country (e.g., through the Ph.D. program, etc.).

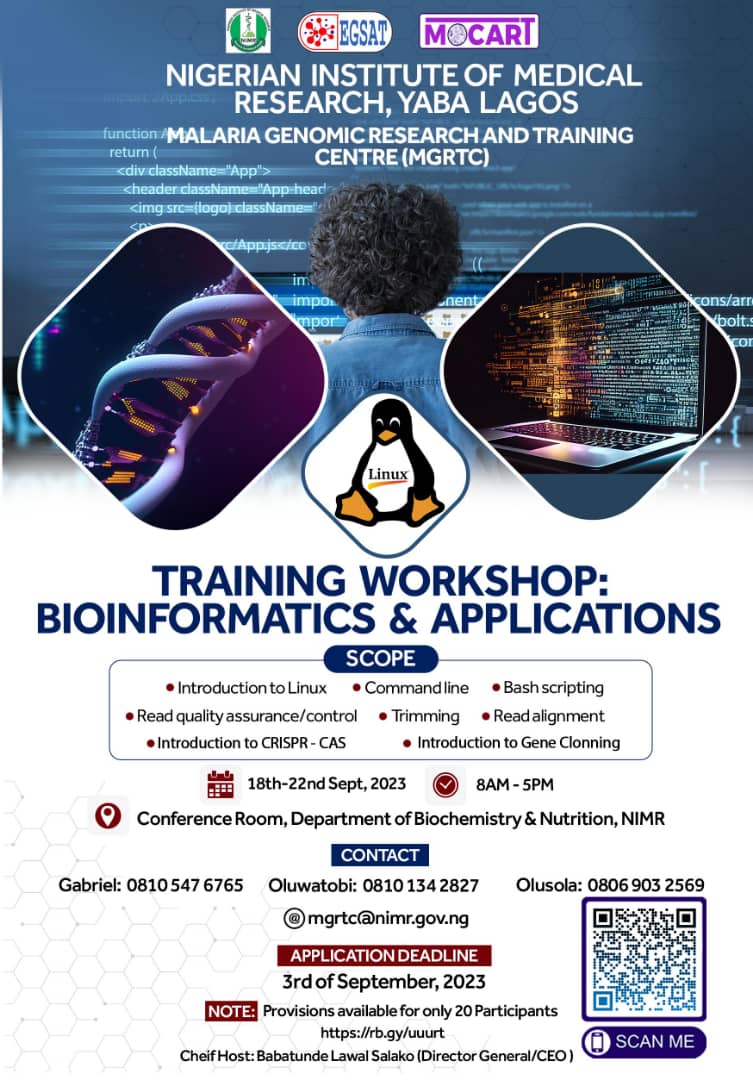

What NIMR researchers can draw from this is that collaboration with institutions outside the country could build local researchers’ capacity. This could be through visiting scholars, whether in the USA or the United Kingdom, to gain new experiences, to collaborate or learn new skills, or through advanced learning in a Master’s, Ph.D., or certificate program through this north-south collaboration. So, I think that is one thing NIMR needs to take advantage of, and this means that we need to broaden our horizon in building collaborations with institutions outside Nigeria and explore how to improve our existing relationships with these institutions. Hence, NIMR, in the long run, will be able to build the capacity of researchers, especially junior and early career researchers, on how to improve their career, skill and be internationally relevant.

What advice would you give to other young researchers considering traveling abroad for research purposes?

As a Chief Research Fellow, my role could include providing guidance and advice to young researchers considering traveling abroad for research purposes. While I may have little direct assistance to offer, I can certainly provide valuable counsel to point them in the right direction and advise them on enhancing their research skills through north-south collaborations. But I would like to encourage young NIMR and aspiring researchers to believe there are possibilities everywhere. Hence, this is an excellent time to go online and browse for these possibilities.

Allow me to share my personal experience to illustrate the potential opportunities available. In 2014-2016, I pursued a Master’s degree at the London School of Hygiene Tropical Medicine, and I was fortunate to secure funding through the African-London-Nagasaki Scholarship program. Interestingly, I became aware of this scholarship opportunity through a friend who forwarded me an email. A wise colleague once advised me that there is nothing to lose by applying for such opportunities, especially when they don’t require any upfront payment. Initially, my application was unsuccessful, but I persisted and advanced to the second phase in the subsequent year. Although I didn’t receive a full scholarship for a Master’s degree, I was offered the opportunity to pursue a certificate course in clinical trials. I completed the certificate course and, during its conclusion, I applied for full funding to obtain a Master’s degree in Clinical Trial, which I completed through distance learning.

I advise young researchers to remain open-minded, keep their eyes wide open, and continue applying for funding opportunities. While it may take time and persistence, fortune may eventually smile upon them, and they can secure the necessary funding to advance their research aspirations.

from Saint Louis University

from Saint Louis University